Healthcare has become undeniably unaffordable for companies, employees & their families.

This is how you take back control.

Build a Bespoke Health Plan

Easily transition for immediate & long-term savings. Mirror the plans you have today, access turn-key solutions & implement the right stop-loss, pharmacy strategy & $0 cost care options.

Build a Bespoke Health Plan

Easily transition for immediate & long-term savings. Mirror the plans you have today, access turn-key solutions & implement the right stop-loss, pharmacy strategy & $0 cost care options.

Deliver a New Service Model

A hospitality-style service model is people-centric.

We focus on the member first - guiding employees through the healthcare system with personal advocates for access to the right providers, fair pricing

& quality care.

Deliver a New Service Model

A hospitality-style service model is people-centric.

We focus on the member first - guiding employees through the healthcare system with personal advocates for access to the right providers, fair pricing

& quality care.

Manage & Control Claims Costs

Gain visibility to control the cost of the claim before it is paid. Lower plans & favorably impact stop-loss costs with proactive claims management.

Manage & Control Claims Costs

Gain visibility to control the cost of the claim before it is paid. Lower plans & favorably impact stop-loss costs with proactive claims management.

Gain Actionable Data

Make informed decisions with access to vetted solutions. Choose the right strategy with plan performance reviews, data visibility & real-time management.

Gain Actionable Data

Make informed decisions with access to vetted solutions. Choose the right strategy with plan performance reviews, data visibility & real-time management.

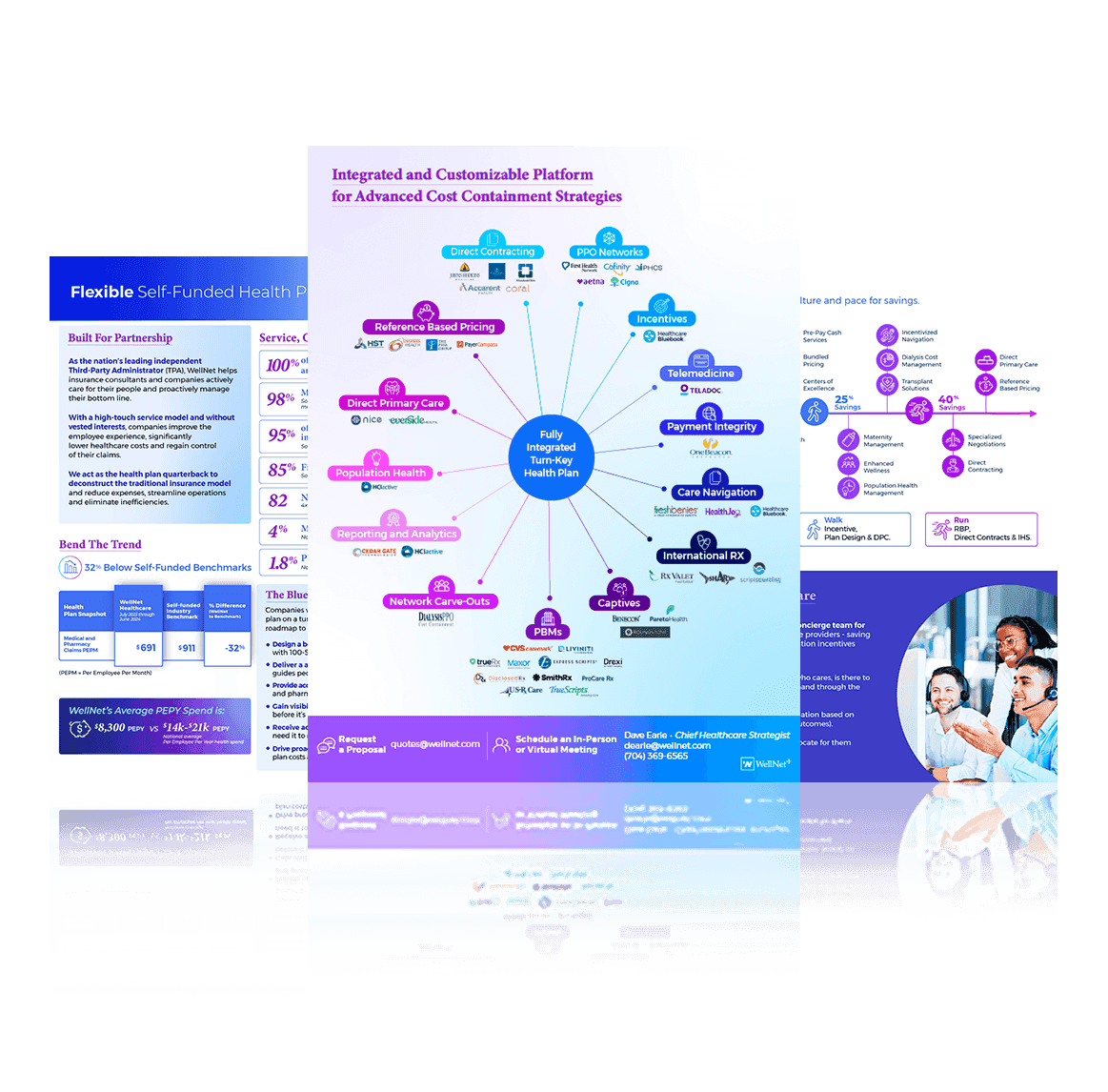

Go At

Your Own Pace

Custom plans use a 20+ point toolkit to fix, repair & upgrade your health plan. We call it Crawl, Walk, Run - knowing each company has its own pace, unique culture & blueprint for savings.

Go At

Your Own Pace

Custom plans use a 20+ point toolkit to fix, repair & upgrade your health plan. We call it Crawl, Walk, Run - knowing each company has its own pace, unique culture & blueprint for savings.

Significantly Improve Outcomes

Employees utilize a healthcare concierge team for guidance - saving companies 10% with care navigation incentives & creative plan designs.

Significantly Improve Outcomes

Employees utilize a healthcare concierge team for guidance - saving companies 10% with care navigation incentives & creative plan designs.

How Companies Bend The Trend

How Companies Bend The Trend

Download the quick-hit guide to rebuild health plans that improve the employee experience, significantly lower healthcare costs & reduce high-cost claims.

Explore WellNet

Actively care for your people.

Proactively manage the bottom line.

One Solution.

Integrated & customized for advanced cost containment strategies.

One Solution.

Integrated & customized for advanced cost containment strategies.

WellNet+

- Level-Funded & Self-Funded Health Plans

- Steerage Incentives

- Billing Errors

- International Rx Sourcing

- Medicare Eligible

- Pre-Pay Cash Services

- Advanced Imaging Carve-Out

- Dialysis Carve-Out PPO

- Direct Primary Care

- Direct Contracting

WellNet+

My Advocacy

- Expertly Trained Personal Advocates

- Real-Time Support & Ongoing Assistance

- Access to Quality Care & Free Resources

- Direct Savings on High-Cost Speciality Drugs & Procedures

- Manage Claims, Billing & Scheduling

My Advocacy

Blade

- Toolkit Analysis

- 20+ Performance Optimizers

- Enhance Plan Design

- Drive Down Claims Costs

- Proactive Pharmacy Management

Blade

Service, Outcomes

& Savings

Service, Outcomes

& Savings

Your on-demand resource center for all the best content - all in one place.

Start here for the best of WellNet content.

Come back for the latest & greatest.

“Control & transparency offered by WellNet are important in creating issue resolution and proactive cost management.”

Carlos Castresana -USI Insurance Services

The New Power Half-Hour

The New Power Half-Hour

Schedule a brief huddle to quickly learn more about how WellNet health plans save money & improve outcomes.

Like what you hear? Keep the convo going with a deep dive at your convenience.

Schedule a brief huddle to quickly learn more about how WellNet health plans save money & improve outcomes.

Like what you hear? Keep the convo going with a deep dive at your convenience.

Crawl, Walk, Run

Tailored for your unique culture

& pace for savings

Supercharge Your Outcomes

Supercharge Your Outcomes

Inside: 20+ ways our performance optimizers control the cost of the claim – before it’s paid.

Ask Us

Anything

Ask Us

Anything

If you’re interested in learning about WellNet solutions, reducing pharmacy costs, improving member advocacy, or simply want to dive deeper into self-funding education, we’re here to help.